Singapore pioneered a basic form of urban congestion pricing in 1975, and introduced what is

still the most sophisticated, economically rational

and effective congestion pricing in the world in 1998, called ERP (Electronic Road Pricing). In 2020 it is transitioning its operating technology to GNSS On Board Units (albeit to initially apply the same mix of corridor and cordon charging as applies today, but with the focus on delivering more information about pricing, traffic, parking and alternative modes through the system).

However, if you've been following the recent very public debates and commentaries about congestion pricing in the USA you'd be excused for thinking it is new and innovative. Innovative it is, it is just that the US has come a bit late to the concept, but what is driving it is not so much congestion, but the desire to use congestion pricing to raise revenue - typically

not for roads.

For many years congestion pricing in the USA has largely been referred to in the context of express/HOT/toll lanes. Although such lanes offer options to pay to bypass congestion on some highways, they are not "comprehensive" in addressing congestion and more importantly are not technically able to be implementing except on roads with limited access. In most cases they have been implemented by converting high occupancy vehicle lanes to HOT/toll lanes. It is rarely economic to build new lanes and charge just for them (because there is insufficient willingness to pay for the capital costs of new capacity, particularly when such capacity may only be utilised for short periods during weekdays), so HOT/toll lanes are rarely seen outside the USA.

The positive example of toll lanes is that they demonstrate that the instrument of price is effective in managing demand so that a road can operate in free flow conditions, but of course such lanes are not practical on most roads and they always have an unpriced alternative. At best they offer an option in some cases, and demonstrate the concept.

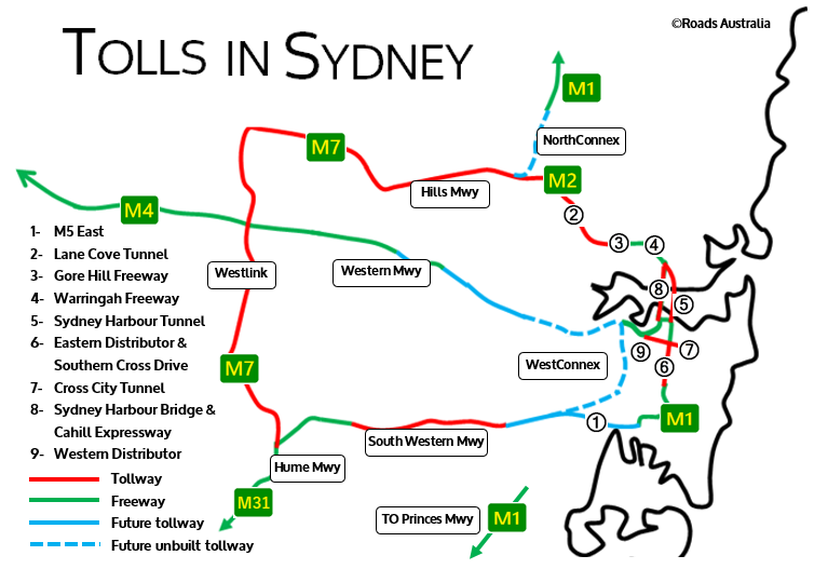

So full congestion pricing has not been seen in the US to date. By that I don't mean having peak pricing on an existing toll road to spread demand on that road (this is seen on many crossings, such as the Golden Gate Bridge, E-407 Toronto and the Sydney Harbour Crossings), but rather pricing of a network or placing a cordon (either on its own or as an area charge) on a zone, with priced access at set times/days.

This isn't common as all. Although there are many low emission zones in European cities (which prohibit or heavily charge vehicles that don't meet low or ultra-low emission standards) and restricted access zones to cities (this is seen in many Italian cities, keen to preserve historic centres of cities ill suited to large volumes of vehicle traffic), the only cities that charge a network or a zone for access on a significant scale are:

- Singapore

- London

- Stockholm

- Gothenburg

- Milan

- Dubai

- Tehran.

There are a handful of smaller examples, Oslo transitioned from a cordon set up for revenue raising to one that has a congestion management purpose now, but by and large congestion pricing is hard to implement. It's been investigated in multiple cities in the UK (Bristol, Cambridge, Leeds, Manchester, Edinburgh) and elsewhere in Europe (Dublin, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Helsinki), but has always come up against one major issue - public opposition.

What has woken up the US?

How about the US then? Suddenly cities, states and the media have discovered congestion pricing because of one simple reason - New York is going to do it. This follows

previous attempts to introduce it, most notably by former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who had his proposal for a cordon on lower Manhattan vetoed by the State Legislature.

The New York Senate and Assembly have approved it, along with the State Governor. The details are to be worked out by a new Traffic Mobility Review Board, but it is essentially a cordon that starts at 60th St, excluding FDR Drive and the West Side Highway. All of the net revenue is to spent on the public transport network, specifically the subway, bus network, the Long Island RailRoad and Metro-North. Private cars are only to be charged once a day, whereas ridehailing/sharing and taxi services

are already subject to a surcharge of between US$0.75-US$2.75 per trip, depending on the service since 2 February 2019. Although

Charles Komanoff indicates that the effects will be much less than promised (still a 2.5% increase in average traffic speeds is worthwhile).

Some of the details to be worked out include:

· Charge rates (will they vary by vehicle type)

· Area charge (will vehicles be charged for circulating within the cordon as well as or separately from crossing the cordon)

· Direction of charge (will there be a charge for entering AND exiting the cordon)

· Time of operation

· Variation of charge by time of day

· Discounts and exemptions (it might be fair to assume that emergency vehicles and NYC transit vehicles might be exempt, but will the ride hail/share surcharge liable vehicles be exempt too)

· How those entering lower Manhattan on tolled crossings will be treated

New York is basically implementing a simple charge, primarily to raise revenue for other modes, so it will be interesting to see what impact it has and whether it is designed to spread demand by time of day, as much as it is to raise revenue. It will clearly be a trailblazer, although it is unlikely that other US city has either the density of public transport or geography to lend itself to a relatively simple cordon as the solution.

What about the rest of the US?

San Francisco has studied charging before, and looks like pursuing it again. The San Francisco County Transportation Board Authority voted earlier this year to spend US$0.5m on a study of downtown congestion pricing, suggesting that it has already decided that a downtown cordon is worth pursuing. It will be interesting to see what impacts that might have, and particularly how boundary issues are addressed. The

San Francisco Mobility Trends report indicated that "vehicular traffic entering San Francisco grew 27% since 2010, although public transport use also rose 5% and cycling by 6%, on a 9% population increase (indicating that the growth in population is pushing a big increase in driving), with a decrease in private car travel speeds by 23%. It's hardly surprising that pricing access to downtown is a priority, although hopefully it will mean pricing that varies by time of day.

Los Angeles has already had a study released by Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) which proposed a pilot cordon at Westside LA, for a number of reasons (see page 94 of the below report).

|

| Proposed Westside LA cordon from SCAG study |

The Mobility Go Zone and Pricing Feasibility Study indicated that it could result in a 19% drop in private cars entering charged zones, and a 9% mode shift to public transit, with 7% each to walking and cycling. Whilst this might be a good place to start, LA is going to need a much more comprehensive solution to address congestion across the region. LA Metro is about to launch a study that looks more widely at options, with the intention that pricing would support a package of improvements to public transport and active modes.

Boston, Portland, Seattle and Washington DC are all considering congestion pricing, which has to be welcome. The US has gone through a couple of eras in urban transport policy, from the 1940s to the 1970s the focus was almost entirely on building roads to meet demand. That has tailed off, with a focus from the 1970s of building (mostly rail-based) public transport infrastructure to try to attract motorists from their cars, in other words supplying alternatives. More recently, cycling has had a boost in some cities, but the primary argument in all cities is one of what to supply, rather than how to manage existing demand and supply.