The big road pricing news in New Zealand in the past week was the Mayor of Auckland, Wayne Brown, calling for congestion charging and appearing on media declaring how critical it was for the city. This was not in terms of raising revenue, but in addressing congestion. On Radio NZ he said Auckland could not afford another motorway, and that the charge would be avoidable by driving outside of peak times.

“I am of the view that this should be on our motorways in the central areas of Auckland, which are the most congested, and this is also where public transport works best, which gives some people an option rather than paying the charge”

He ridiculed concerns about equity around trade businesses, saying that to pay $5 to save 20 minutes was a small fraction of the price the tradespeople charge their customers in an hour. He also said that schoolchildren “don’t’ have a right to be taken to school in a BMW” and more should walk, bike or use public transport.

The Mayor was elected in 2022 and has a three year term, but his support for the concept was only solidified when Auckland Council voted 18-2 in favour of setting up a team to oversee implementation of congestion charging.

Despite that report, Auckland is not going to get congestion pricing in two years. Legislation will take around a year to introduce and pass at best, and it will take around 18 months to procure and install a system at best. However, you have to admire the ambition.

The astonishing level of local political support for the concept is unheard of in any other city where the private car is by far the dominant transport mode. In 2018 (according to the Census), around two-thirds of Aucklanders commuted by car (whether as driver or passenger), 11% by bus, 9% walked and 8% worked from home, 3% by train and just over 1% by bicycle. It seems likely that the proportion working from home, cycling and using public transport has increased since then.

Let's be clear to those unfamiliar with Auckland. The Mayor is ostensibly "centre-right" and got elected opposing the "war on cars". The Council as well is fairly balanced between left and right wing members.

Unlike New York and almost all other US cities that have been investigating congestion pricing, Auckland is regarding the net revenues as secondary (although the Mayor is interested in revenue, as the incoming government has pledged to abolish the regional fuel tax of NZ$0.10 per litre that raises revenue for transport projects in the city). The primary focus is reducing congestion and encouraging behavioural change. However, it would clearly generate net revenue and would also have positive environmental benefits.

Why does this matter?

All of the cities that have introduced congestion pricing around the world so far have been quite different from Auckland, and indeed all of the predominantly car-oriented low density cities that are seen in New World cities in New Zealand, Australia and North America. Singapore, Oslo, London, Stockholm and Milan all have significant mode shares for public transport. However, Dubai and Abu Dhabi (and soon Doha) are car dependent cities, even moreso than Auckland, whereas Gothenburg in Sweden is much closer to the mode shares seen in New World cities.

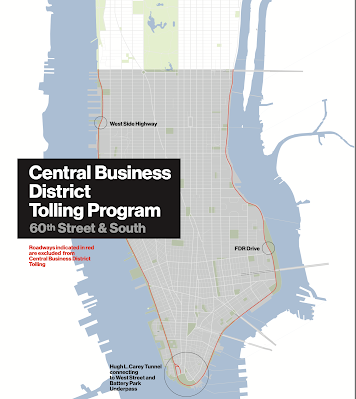

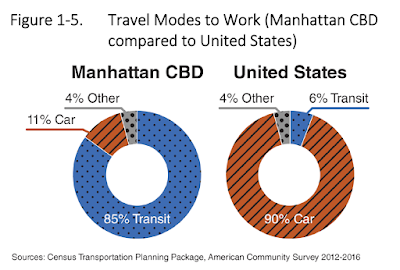

Although New York will be the first US city to introduce some form of congestion charging, it is being implemented in lower Manhattan, which is much more like central London than most US cities, and it is being introduced 24/7 (with peak charges) primarily to raise revenue. New York is not a model for other North American cities.

Auckland on the other hand, has around 87% of its employment outside the central city, it has around a 50% mode share for public transport and active modes for trips to the central city at peak times, but a much lower mode share for trips to other parts of Auckland at peak times. In short, congestion in Auckland is primarily about trips across the city, not to the downtown. Pricing in Auckland will work only in part by encouraging modal shift, but will in a large part be about encouraging a small proportion of trips to shift time of day or frequency of driving.

Furthermore, unlike many other developed cities, Auckland has had over 20 years of billions of dollars in continuous major capital spending on its transport networks. During that time, the road network has been significantly upgraded, with additional lanes on motorways and a ring route around the west bypassing the congested central motorway junction. The commuter rail network was extended to the downtown, electrified with new trains, adding new lines, and is now being expanded with an inner city loop. Bus services have been expanded, with busways and new buses, routes and expanded frequencies. In short, Auckland has seen extensive capital spending on its transport infrastructure and it has been unable to keep up with demand, and congestion has not been resolved.

Supply of transport infrastructure does not sustainably reduce traffic congestion.

If Auckland successfully implements congestion pricing, it will be a world leader in implementing road pricing in a city with automobile dominance.

What has been proposed?

The Mayor has specifically proposed a charge on two segments of motorway of NZ$3.50 - $5 per trip. It would operate in the AM and PM peaks only on the North Western Motorway (SH16) between Lincoln Road and Te Atatu Road, and on the Southern Motorway (SH1) between Penrose and Greenlane. These are two of the most congested parts of Auckland’s motorway network. The map below depicts the short section of North Western Motorway, the segment of Southern Motorway and the earlier proposed downtown cordon (which is bypassed by the motorway network which goes from south to the Auckland Harbour Bridge and from the west to the Ports of Auckland).

|

| Auckland congestion pricing concepts. |

Undoubtedly the motorway proposals would have a positive impact. While the North Western motorway at this location has no reasonable alternative route, the Southern motorway does have a wide at-grade arterial road, albeit with multiple sets of traffic signals and a much lower speed limit. Some measures would need to be taken to minimise diversion onto the parallel routes.

It's worth noting that a major study into congestion pricing in Auckland, called The Congestion Question, was carried out from 2016-2020, and recommended that a downtown cordon be introduced, followed by corridor charges on major routes in the isthmus and beyond. The Mayor is proposing the second stage, but that is good as the downtown cordon concept was likely to have a less dramatic impact than the proposed corridor charges.

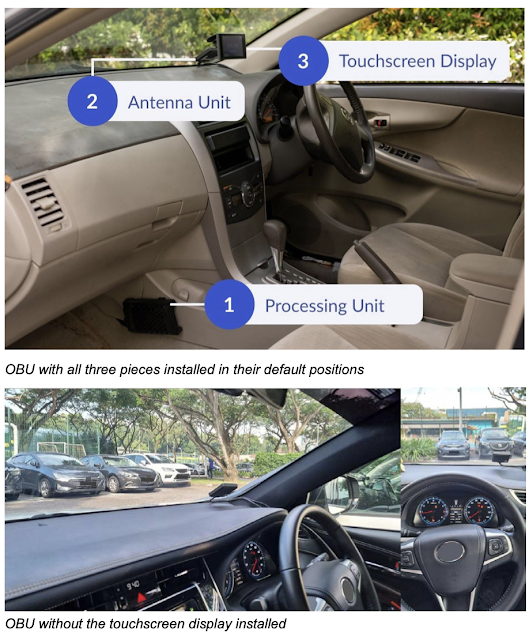

The proposed technology would be automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras.

What needs to happen?

- Don't see London as an example to copy. London is an area charge, it has a flat all day rate and has not enabled traffic to flow relatively efficiently for over 10 years because it is too blunt. London may be seen as culturally closest to Auckland, but it is vastly different. Better examples are in Singapore and Stockholm.

- Don't make this project about raising revenue. When the focus becomes revenue raising, the design will change and it becomes a lot more difficult to get the public on-board, because you are designing a tax, rather than a traffic management and pricing scheme.

- Don't make this about reallocating road space. While there will be localised cases where there is merit in doing this (specifically for cycling safety or bus priority at intersections), a successful congestion pricing system should enable all traffic to flow efficiently, including buses, and will improve conditions for all modes on the roads. Some advocates for congestion pricing see it as a tool to penalise driving and to make it more difficult for motorists to drive. If this is the policy adopted, it will be rejected by the public (as it has been in many many cities), as pricing need not be a tool of penalty, but a tool to make existing networks work better.

- Don't play with technology yet. There would be nothing wrong in eventually linking the current eRUC telematics systems to congestion pricing so their users (almost all commercial vehicles) pay charges automatically, alongside RUC. However, ANPR is just fine for now.

- Don't make any announcements on details until you have decided on most of them, and have responses as to why you made certain decisions. Don't let the media and public discourse determine policy. Design a good system with defensible policies, and then present it to the media and public, so you can make clear what might be negotiable and what is not. A litany of failures elsewhere are due to letting policy debates get out of control, raising fears and uncertainty, and consigning the concept to the "too hard" basket.