The recent news that the New York lower Manhattan congestion pricing proposal has received Federal endorsement (which was needed as some of the roads to be charged are Federally funded) seems likely to be the last major barrier before the proposal can be actually implemented. It has taken some time, not least because the Trump Administration neither progressed nor rejected the proposal.

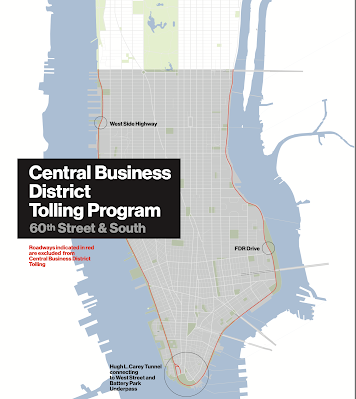

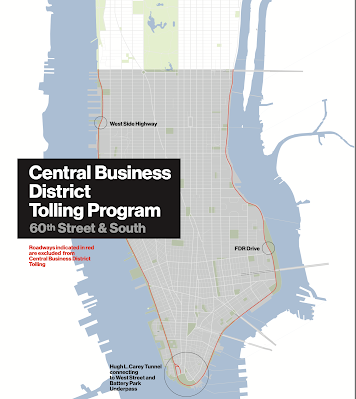

The proposal is basically an area charge around lower Manhattan, which is called the New York City Central Business District Tolling Program. This is a fair title as it probably isn't sophisticated enough to really justify the term "congestion pricing" although it should reduce congestion, it is essentially designed to raise revenue.

|

| New York congestion pricing concept map |

There are some oddities about the proposal, notably that the road around the periphery of lower Manhattan is exempt from the charge, when for almost all trips is only worth driving on to access the zone within it. It is notably also an area charge, which is a concept only implemented elsewhere in London (and then it was only because the Automatic Number Plate Recognition technology in 2003 had such a poor read reliability rate that the target was to get each vehicle to pass around three sets of cameras to be sure it would be identified). So it will charge vehicles entering AND vehicles remaining within the area during operating hours.

Key characteristics

Vehicles will only be charged ONCE per day, so it won't penalise frequent movements (this will appeal to commercial traffic, but should dissuade some occasional traffic and regular commuters).

Residents earning less than US$60,000 a year will get a tax credit for tolls paid, essentially a low income exemption for residents of the zone. It is currently proposed that a 25% discount would apply for low-income frequent drivers on the full CBD E-ZPass toll rate after the first 10 trips in each calendar month (excluding the overnight period)

Emergency vehicles and vehicles used to transport people with disabilities will be exempt (the latter category could be quite extensive!).

A new entity called the Traffic Mobility Review Board would recommend the rates table, with prices to vary by time-of-day with a mandate to consider how traffic might move, effects on air quality, costs, effects on the public and safety. Indications are that prices could be between US$9 and US$23 depending on time of day, with overnight charges of US$5.

Rates from midnight till 0400 must be no more than 50% of that of peak charges (you may question why there is a fee at all at that time, but this is because the main objective is revenue).

Drivers paying existing river crossing tolls (not all river crossings have tolls) will get those tolls credited to paying the Lower Manhattan charge.

Charges will be levied by detecting E-ZPass toll tags. Vehicles without toll tags will be charged through Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras which will be used to identify the vehicle's owner through Departments of Motor Vehicles, and be mailed to the owner.

$US$207.5million is committed over five years to mitigate negative impacts including the low-income discount, monitoring of traffic, air quality and transit stations,

Objectives and expected results

Officially the goals are:

- Reduce daily vehicle-miles traveled within the Manhattan CBD by at least 5 percent.

- Reduce the number of vehicles entering the Manhattan CBD daily by at least 10 percent.

- Create a funding source for capital improvements and generate sufficient annual net revenues to fund $15 billion for capital projects for the MTA Capital Program

- Establish a tolling program consistent with the purposes underlying the New York State legislation entitled the MTA Reform and Traffic Mobility Act.

1. Net revenues! 80% of net revenues will be used to improve and modernise New York City Transit (subway and buses), 10% to Long Island Rail Road, 10% to Metro-North Railroad. Zero revenue will be used to support even maintenance of the roads being charged let alone improvements to them. In effect, it is a transfer from motor vehicle operators to transit providers and their customers. Around US$1 billion in net revenues is expected.

2. Reducing congestion (although no formal targets have been set). From the document filed with FHWA, It is expected that there would be a 15-20% reduction in daily vehicles entering the charged area. Commuter car trips are expected to drop by 5-11%. Notably through trips by trucks are estimated to drop by between 21 and 81% (these are trucks with no origin or destination in the zone). Public transport trips are estimated to increase by 1-3% in the area. The net effect outside the charged area is expected to be a reduction of 0-1% in overall traffic volumes. Effects on active travel are expected to be small. Taxi trips are estimated to change ranging from a 1.5% increase to a 16.8% decrease in trips.

There are also intended to be modest improvements in air quality, but this is largely not being highlighted.

New York is fairly special

Lower Manhattan is unlike much of New York, let alone other US cities. It has much more of the characteristics of central London, than indeed most US downtown areas, and it has a density of public transport availability that is unmatched in any other US city. This ought to make it the easiest location to implement congestion pricing, (even though it is pricing road use 24/7). 617,000 people live in the Manhattan CBD, but 80% do not own or have ready access to a car, this compares to 9% across the USA. That is primarily by choice, because of the walkability of so much of this relatively densely developed area, the availability of public transport options, and the lack of parking for residents' vehicles.

|

| Manhattan car ownership compared to the US |

Approximately 1.5 million are employed in the Manhattan CBD, of which 84% typically commute from outside the CBD (pre-Covid). 65% commute from other suburbs of NYC, 18% from New Jersey, 8% from Long Island, and 7% from other New York counties. 85% commute using public transport, 11% by car and the remainder by active modes, taxi/rideshare vehicle. Again this is completely unlike commuter patterns elsewhere in the United States.

|

| Manhattan commuter mode shares |

The value of time of congestion lost in New York is estimated to be US$1,595 per driver per year in the NYC region, equal to 102 hours of lost time. On one measure bus speeds have dropped 28% in the Manhattan CBD since 2010.

However it is far from being all about commuters, the data also indicates that 7.7 million people enter and exit the Manhattan CBD on an average weekday, 75% by public transport, but 24% by car, taxi, ride share vehicle or truck, indicating that there is a far more significant problem of all day travel in Manhattan than commuter peaks. This has parallels with other large dense cities such as London, whereby the motor vehicle traffic is largely not AM/PM peak commuter driven in the city centre. The numbers of vehicles entering Manhattan CBD each weekday is equal to the entire population of Phoenix, AZ.

The profile of this motor vehicle traffic is astounding.

|

| Profile of Manhattan CBD vehicle entry/exit |

Volumes do peak inbound in the AM, but largely stay steady from noon until 2200 and outbound trip peak at 0700 and grow slowly until 1600 and then only drop off significantly after 2200.

This explains the desire to have charging across the day (although 2300-0500 seems excessive).

This also explains why New York is special, as most other US cities do not have a CBD anywhere near as dominant or dense as New York. While most have a central business district of some importance (see Chicago, Washington DC, San Francisco), and could implement some sort of cordon or area charge in such locations, the scale and density of traffic in those locations does not match that of lower Manhattan. Furthermore, it is critical to understand that any schemes would be unlikely to have a significant affect on traffic more widely across those cities. That's because most traffic movement in US cities does not starting or terminating in the downtown, but rather criss-crossing smaller commercial centres and locations of employment, as people live and work in a vast array of different places. US cities in most cases are highly dispersed.

Even the New York scheme is not expected to have a significant impact on traffic beyond Manhattan, with an estimated reduction of 1% across New York City more widely.

So if congestion pricing is to be implemented primarily to resolve congestion, unless the focus is the downtown area and roads approaching it, a downtown cordon is unlikely to achieve much from a network point of view.

This is not to say there is not merit in targeting car trips to downtown areas at peak times to reduce congestion in those areas and encourage modal and time of day shift (and as a result free up some road space on corridors approaching those areas). There certainly is, but congestion pricing has proven extremely difficult to implement in the US because there is excessive focus on revenue raising to support public transport, rather than improving the level of service for those paying to use the roads.

In US cities it is much more likely that significant improvements to congestion will be achieved not by pricing access to downtown areas, but by pricing corridors (and ultimately pricing whole networks). Corridor pricing, as seen in Singapore, is much more likely to encourage the behaviour shift needed to optimise throughput on congested roads. However to understand that, city planners and politicians have to broaden understanding of congestion pricing being just about encouraging modal shift, for it is just as much about changing time of travel and frequency of travel. Indeed in US cities it is likely to be moreso. In Stockholm, the data on behaviour change for that relatively large inner city cordon, indicates that only 40% of the reduction in car trips during charged periods was attributable to modal shift. That is certainly important, but the remainder is a whole set of other behaviours including:

- Shifting driving time from the peak period to the off-peak period (with lower charges) or uncharged period either in one direction or both directions of travel.

- Reducing frequency of driving, by consolidating appointments and activities into fewer trips. This means the same productive activities were able to be carried out with less frequent driving.

To date the main policy focus from cities in the US wanting congestion pricing has been an eye on revenue, which is understandable, as there is a lot of potential to raise money. However, public acceptability is rarely built upon what is seen as a new tax. Lower Manhattan is special because most people who live there don't have a car, and most people who commute or travel into it, don't do so by car, but although none of the net revenues will be used to directly benefit those paying, there IS a focus on achieving results in terms of reduced congestion.

The Traffic Mobility Review Board is a good measure to ensure that the policy and rate setting around the scheme will deliver net benefits, although the membership of the Board is required to have one member recommended by the Mayor of the City of New York, one member reside in the Metro-North Railroad region, and one member in the Long Island Rail Road region. The board composition is

available here.

My expectation is that there will be more studies on congestion pricing/charging, but getting public acceptability for it will continue to prove difficult. That is because far too many developing such programs are focused on raising revenue, without thinking about how pricing can improve conditions for those who still drive (New York has not ignored this). Some ignore the enormous benefits pricing can deliver to improving bus capacity and reliability, just because of reductions in congestion. Finally, far too many look at a program like New York (or London) and just try to copy it, rather than thinking more broadly about the ways congestion pricing can be implemented on a road network. There are far better examples than London, and more sophisticated systems and policies in place in cities such as Stockholm and Singapore, but it is entirely possible to do something quite different, and be effective.

Congestion pricing needs to be led by policy objectives and be tailored carefully to local conditions. A key reason it failed to expand in the UK beyond London is that too many advocates did not seek to design to target congestion, but to target potential revenue, and far too many wanted to communicate to those who they wanted to spend net revenues on, not those who would pay.

After all, congestion pricing that doesn't reduce congestion is just another tax.

What next?

The scheme can be implemented around early to mid 2024, after contractors, design, build, install and test equipment to be installed at the roadside. Meanwhile the Traffic Mobility Review Board will develop recommendations for a rate schedule, which will need to be approved by the MTA Board for public consultation and hearings, before final decisions are made.

It can only be hoped that its implementation is a great success, that it meaningfully reduces congestion in lower Manhattan (and the routes approaching it), that this improves air quality and improves mobility overall, and helps to catalyse thinking across the United States about the merits of congestion pricing.

However, most of all I hope it catalyses thinking about how congestion pricing needs to be tailored for each city, to meet its needs, its objectives and to develop the public acceptability needed to avoid it being a major controversy.