None of this will be news to readers of this blog. The key point being that it is almost impossible to sustainably address traffic congestion in major cities by simply building capacity (paid for largely by those not using that capacity) to meet demand, whether it be capacity on roads or on public transport (which is commonly seen as the main way to attract traffic off of roads). It cites the avoidable costs of congestion from a BITRE study of (Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional

Economics) of A$6.1 billion in Sydney and A$4.6 billion in Melbourne. This is a figure imputed from the costs of lost travel time (and vehicle operating costs), but is still an economic drain. There is no plausible way of significantly reducing these costs without pricing to spread and moderate demand.

I think the report provides a quite compelling case for congestion pricing in Sydney and Melbourne. It particularly includes research and data that is pertinent to other "new world cities", characterised by largely low density population and land use, high private car ownership and usage and dispersed employment locations. Many assumptions that may be widely held among decision makers and the public should be challenged by this report.

Some of the highlights are the following:

- In the morning peak up to 21 per cent of trips on Sydney roads are for socialising, recreation, or shopping (i.e. not commuting, or trips to education) (p.8). This infers that the scope to price some of those trips onto other modes or at other times should be significant, and more importantly, even a drop of a quarter of those trips would likely have a noticeable effect in reducing congestion). (The figure for Melbourne is 11%). It also might infer that the elasticity of demand for those trips in the morning peak is greater than for others, but this ought to be established by further research;

- There is record spending on urban road and public transport infrastructure in major cities (over A$35 billion in the current year), indicating that it isn't a lack of spending on supply that is the issue (p.12), and the majority of committed spending is on public transport (p.8). Quite simply, building more capacity will never be enough (and the value of that spending continues to drop);

- ANPR technology is now the most feasible option to use for cordon and corridor charging (p.13), as toll tags are increasingly unnecessary;

- There is insufficient use of "repurposing road space", which can be used to increase overall capacity or provide dedicated capacity to specific road users. On average, 14% of road space can be reallocated (typically to cycling and pedestrians) without reducing overall capacity (p.22);

- Parking levies have very limited impact (A$2490 for Sydney CBD, A$1440 for Melbourne), noting that up to 40% of vehicles in the Sydney CBD are through traffic (compared to a third in Melbourne). (p.25);

- CBD cordons in Sydney/Melbourne could improve speeds by up to 16% in the CBDs and 20% on roads approaching them, and 1% improvement in whole of network speeds (pp.28-29), with more details to come in a report next week;

- CBD cordons would mostly affect high income drivers, as it is them who predominantly drive to the CBDs. Only 15% of jobs in Sydney and Melbourne are in the CBD (pp.35-36);

- People on higher incomes tend to drive the furthest to work, 30% of workers live in the suburb they work in, or an adjacent one (p.36). Which may also indicate that charging by distance will mostly affect those on higher incomes;

- Low income drivers with few alternatives can be protected from excessive impacts of congestion charging (p.40).

- The report claims "now is the time" because others are doing it, but this shouldn't be the only determinant. Of the proposals listed, Hong Kong is on hold for fairly obvious reasons, Vancouver's proposals received a very poor public response and are unlikely to proceed, Jakarta's proposals have been fraught with a range of difficulties (which I have written about on this blog). I doubt in the short term whether any US city, other than New York, will advance further given the politics and lack of creative policy thinking (p.10).

The report rightfully (and in contrast to some other reports lately) notes there are broadly three main options for charging:

1. Cordons (this should include area charging), although it only talks about CBD (central city) cordons, when this tool could be applied more widely onto other centres of activity. London (as an area charge), Stockholm, Gothenburg, Milan, Valetta and the future New York and Abu Dhabi schemes are all cordons, and Singapore has one as part of its scheme;

2. Corridor charges, although again this could be wider than a major highway and could include charges on viable alternative routes. Singapore and Dubai both have corridor charges; and

3. Network charges, which it defines only as distance based charging, but actually needs to disaggregate by route and time of day (simply charging all travel at a flat rate by distance within an area wouldn't achieve much in comparison). No city has this for congestion pricing to date, although Singapore will be implementing the technology that could facilitate this in the next year.

The reaction

Sadly I'm not surprised that the political reaction has been poor. With the possible exception of former (Federal) Minister for Urban Infrastructure Paul Fletcher, there is at best a void of interest in congestion pricing in Australia and at worst antipathy which demonstrates fear most of all.

Of course, the experience of London is well known, and there was a flurry of interest in the UK in the five years after London implemented its congestion charge, but other schemes came to nought, for a range of reasons including lack of trust that charging elsewhere could deliver improvements for those paying that were worthwhile, and antipathy towards yet another increase in the cost of motoring.

However, things have changed elsewhere. The United States, where car use is dominant in all cities (except lower Manhattan), now has a flurry of interest in investigating congestion pricing. New York is proceeding, but the jury is out on other cities. Closer to Australia, work has continued on congestion pricing in Auckland (indeed Auckland has had multiple studies on congestion pricing specifically or considering pricing as part of a wider package for over 15 years). The fact that new world cities are seriously considering it ought to mean the same should happen in Australia.

However in Australia the reaction from most circles is a big fat no, which is exactly what came from several sources in the days after the report was released. Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews (who was re-elected in 2018 with an increased majority), who has a strong reputation for action on climate change said (

according to the ABC):

The best way to ease congestion is to build a public transport network system which can deliver more trains, more often — and we're getting it done....We have no plans and do not support a congestion tax.

New South Wales Premier Gladys Berejiklian (who was re-elected earlier this year) said pretty much the same (

according to 7News):

The best way to reduce congestion into the future is to build major public transport projects

The NSW Transport Minister echoed this.

Unfortunately, they are all wrong.

London and Paris have public transport networks that would be the envy of any Australian city, but the simple rule is that large cities cannot build themselves out of congestion with public transport or roads, if pricing is not used as a tool to manage demand.

It is almost a cliché to say "building new roads just generates more demand", but this is in a climate of not applying efficient pricing to that capacity.

But what about the toll roads?

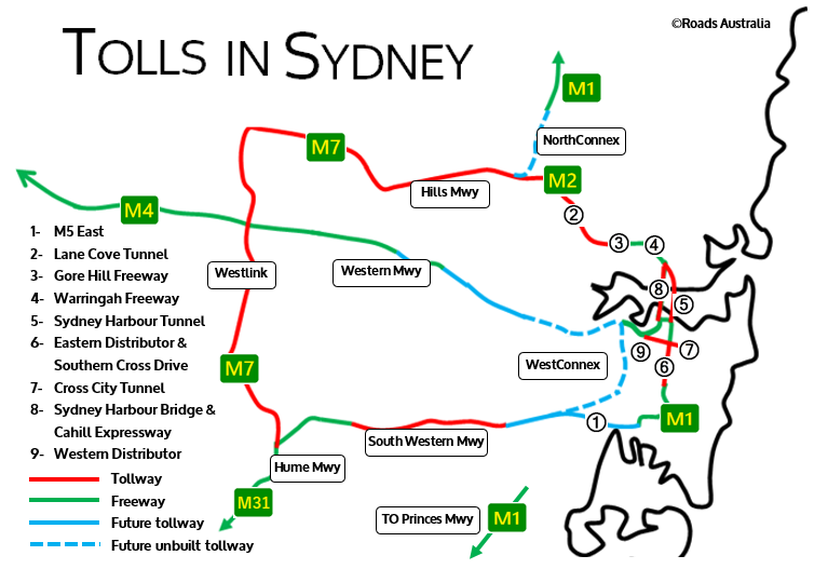

Ah but Sydney and Melbourne have toll roads you say. Yes they do, but only some major roads are tolled and almost none of them have higher prices at peak times (the Sydney Harbour crossings do, but the difference between peak and off peak prices are so small (A$1) as to have a correspondingly small impact).

|

| Road Australia map of Sydney toll roads including those under construction |

The negative for Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane is that residents of those cities are highly likely to see congestion pricing as "just another toll", and media coverage of the issue reinforces this. Because some toll roads are regularly congested, there is likely to be a high degree of scepticism that congestion pricing at modest levels would reduce congestion, when relatively high tolls do not appear to have that effect (but of course they DO have the effect of reducing demand on those roads, but as long as they remain priced the same all day long, there wont be any real difference in demand patterns compared to untolled roads, except parallel routes in very low traffic volume periods). Furthermore, as many toll roads are private concessions with concession agreements that limit policy options to constrain the revenue from tolls for the concessionaires, practically speaking it could be difficult to implement congestion pricing on a wide scale without having to compensate investors in those toll roads.

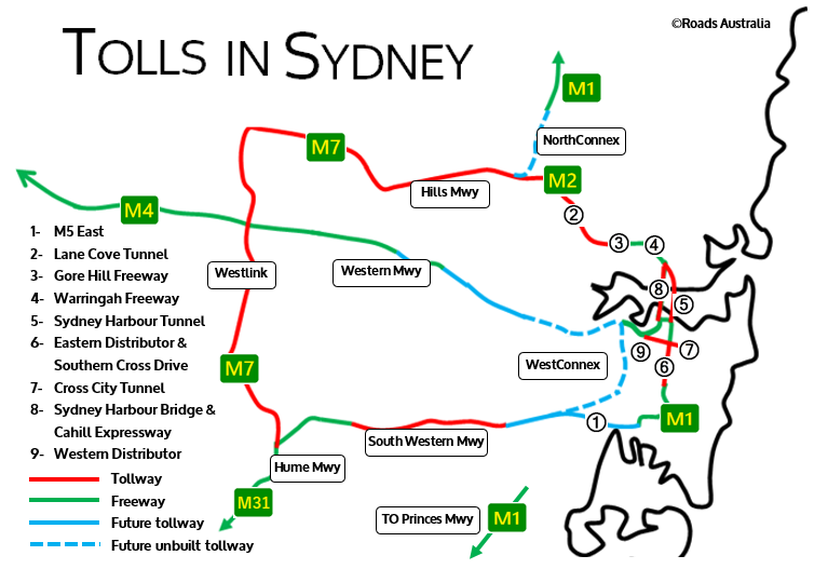

|

| Melbourne toll roads in red |

In other words, tolling is a

negative when it is unpopular and linked to a choice of using a new road which is tolled compared to an existing road. Yes tolls in Sydney and Melbourne contribute to moderating demand, but that effect is not apparent because most toll roads have the same price all day long.

What should happen?

States should investigate congestion pricing as a tool to reduce traffic congestion, sustainably manage demand on the road networks, encourage mode and time of day travel shift (very few commentators really note that part of congestion pricing is changing

when people drive not just

how people travel.

Congestion pricing is obviously thought of as a way of generating more revenue to spend on transport, but it could also be used to replace or reduce existing charges. For example, registration fees could be cut state wide, benefiting those in regional and rural areas who have virtually no transport alternatives. Private vehicle registration fees in Australian state are high compared to New Zealand and US states (e.g. Victoria charges up to A$834.80 a year).

Furthermore, congestion pricing options should be developed based on making noticeable improvements to network performance NOT revenue raising, and the debate about recycling the revenue can proceed.

Be very clear, there will be severe traffic congestion in Sydney and Melbourne for many decades, no matter how much money politicians pour into roads and public transport. It wont be significantly eased without the use of pricing. It's about time that work was undertaken to investigate options, to engage with the public about such options, what they would mean in terms of winners and losers, and how congestion pricing could reduce the burden of registration fees for everyone (much better than the

ludicrous NSW toll relief on registration fees).

What I predict is that Auckland will have congestion pricing by 2025, even on a small scale, but by then the debate wont have moved on in Australia at the political level, if the politicians themselves don't get investigations undertaken about congestion pricing.